As on any other rainy late summer morning in Southern Appalachia, the sun rose over densely wooded, knobby green peaks cloaked in a thick downy mist.

At a large, nondescript warehouse off Swannanoa River Road just outside downtown Asheville, it may have looked like any other day — workers bustling about, trucks coming in and out — but for MANNA FoodBank, which fights food insecurity in a historically poverty-stricken region by serving up to 190,000 people a month, this day would be unlike any other for perhaps the last thousand years.

“We moved our entire fleet of vehicles to higher ground, and we took care of sandbags and things like that, anticipating there was a chance that there could be some flooding,” said Mary Nesbitt, chief development officer for MANNA. “We lifted everything up off of the floor, which is our typical procedure in disaster preparedness. Every single bit of food, lifted three feet off the floor.”

They were 23 feet short.

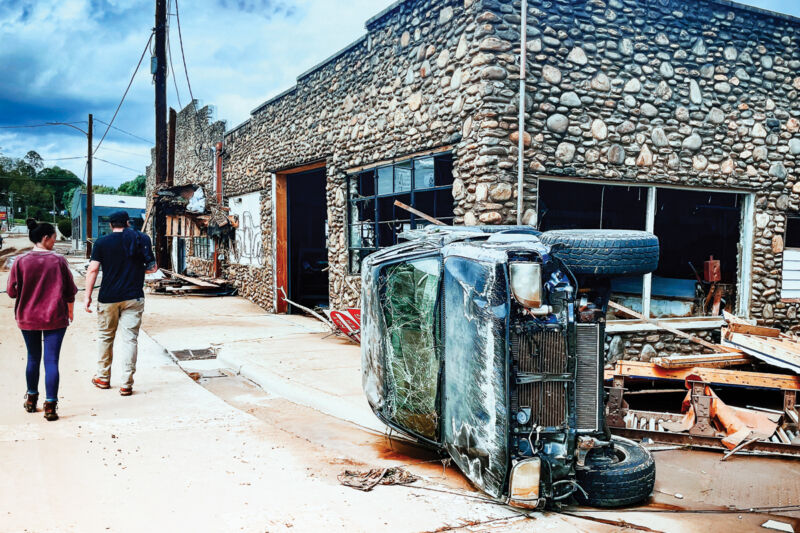

In the hours after Hurricane Helene tore across Western North Carolina on Sept. 27, 2024, the region’s commercial, electronic and transportation infrastructure lay in ruins.

“It was unimaginable, what took place,” Nesbitt said. “I’m getting goose bumps thinking about it, thinking about the magnitude of the hurricane.”

Bridges no longer bridged and roads eroded, some slowly nibbled away by the persistent pressure of waterways that had slipped their banks, others scoured to rubble in a flash. Power and internet failed, leaving even basic communications between first responders, governments and everyday folks next to impossible. Gasoline and grocery shipments ground to a halt, which led to rationing and long lines of irritable people standing in the mucky aftermath of an extreme weather event. Merchants couldn’t accept electronic payments, leaving some customers unprepared and running on empty. Municipal and private water systems failed or were destroyed. Shelters swelled as more than 73,000 homes were damaged.

Emboldened by more than a foot of rain, the mighty Swannanoa River destroyed both of MANNA’s buildings on Swannanoa River Road.

But even before donkeys laden with supplies sauntered into isolated settlements across this rugged region, something else was already moving — philanthropic donations in the tens of millions of dollars.

A good chunk of those donations ended up with The Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, which traces its philosophical roots to a larger early 20th-century movement that created permanent, locally controlled philanthropic institutions pooling charitable resources to meet changing community needs over time.

The Cleveland Foundation, established 1914 in Ohio, is widely recognized as the first community foundation in the world. In 1915, Chicago followed suit with The Chicago Community Trust. Modeled after Cleveland’s example, it became one of the earliest adopters of the community foundation concept and spawned a similar foundation in Boston that same year.

Founded in Asheville in 1978, CFWNC is now one of hundreds of place-based philanthropic institutions across the country, managing a vast portfolio of $481 million in donor-advised, designated, nonprofit and discretionary funds, each created with specific charitable goals in mind.

The foundation’s work typically focuses on four priority areas — cultural resources, education, human services and natural resources. It runs 23 to 25 grants programs that include responsive awards and strategic investments made in partnership with co-investors. Last year, the foundation managed roughly 1,300 funds and awarded $24.8 million in funding.

Some of those funds address broad areas of concern, like the Pigeon River Fund, which seeks to improve local waterway quality by granting to everything from cleanup projects to mitigation to costs associated with land or conservation easement acquisition. The Pigeon River Fund has invested more than $10 million in Haywood, Buncombe and Madison counties since 1996.

Other funds have a narrower focus, like Women for Women, a giving circle that has granted nearly $5.6 million since 2006 to support improvements in the lives of women and girls in Western North Carolina through programs like the Equal Plates project, which provides meals for single-parent families sourced from women-run farms, and the Rutherford Housing Partnership, which helps with safe, affordable housing for low-income women-led households in that county.

Still other funds concentrate on specific places, almost functioning as mini-community foundations by making grants to a wide array of cultural, educational, social or nature-based programs within a defined area.

The foundation administers nine such funds including for Haywood, McDowell, Mitchell, Rutherford, Transylvania and Yancey counties as well as the towns of Cashiers and Highlands, along with a fund for Black Mountain and the greater Swannanoa Valley.

In times of crisis, the foundation’s flexibility and deep community ties allow it to act as a philanthropic first responder.

The COVID-19 pandemic marked a pivotal moment for the foundation’s disaster work. In the early days of the outbreak, the foundation quickly opened its Emergency and Disaster Response Fund to support local health systems, food banks and social services.

By the time Tropical Storm Fred struck in 2021, the foundation already had plenty of experience standing up rapid-response grant programs, awarding more than $290,000 in 2021 and 2022 to affected schools, nonprofits and community organizations.

Early allocations in September 2021 prioritized urgent housing, food and health needs, including $75,000 to the Community Kitchen to reopen its meal program, $95,000 to Mountain Projects for home rehabilitation, and $10,000 each to the Red Cross, Jewish Family Services and the 30th Judicial District Alliance for direct assistance with housing, mental health and medical needs. Smaller community grants, like $2,500 to the Beaverdam Community Development Club, ensured grassroots groups could meet rising demand for food support.

As recovery from Fred progressed, the foundation’s economic and disaster recovery funding shifted toward restoring educational and childcare services disrupted by the flood. Pisgah High School, Canton Middle School and their boosters received a combined $35,160 for technology, equipment and band needs once funded by canceled activities. Smart Start of Transylvania County secured $20,000 to repair damaged learning spaces, while Haywood County Schools Foundation replaced school district vehicles and equipment. Additional support went to Grace Church for rental assistance, United Way of Haywood County for its Recover Haywood program and Mountain Projects for repairs to Canton Head Start and the senior center. Together, the grants reflect a dual focus of meeting the immediate needs of families while investing in the long-term recovery of community institutions.

Although Fred devastated the eastern part of Haywood County, especially Cruso and Bethel, along with parts of Buncombe and Transylvania counties, the impact was relatively contained.

Hurricane Helene was different.

Helene was wider in scope, deeper in impact and longer in recovery than anything the region had seen in modern times. By the time floodwaters receded, entire neighborhoods were wiped out. Public schools were closed indefinitely. Nonprofits that typically served thousands suddenly found themselves with destroyed inventories and ruined facilities.

State and federal emergency response systems were slow to materialize in the face of an estimated $60 billion in damage. According to an Oct. 23, 2024, report by the Office of State Budget and Management, 4.6 million people — about 40% of the state’s population accounting for 45% of the state’s GDP — live in a designated disaster county.

Almost two weeks after the disaster, North Carolina’s then-Gov. Roy Cooper signed the first relief bill presented by the General Assembly. It established the Hurricane Helene Relief Fund and allocated $273 million from the state’s $5 billion “rainy day” fund. Senate President Phil Berger (R-Rockingham) called it a “first step” toward comprehensive recovery planning, although it put no actual money on the street.

Lawmakers approved a second relief package two weeks later, allocating an additional $604 million to the Helene fund. Although the bill targeted a wide range of needs, it did not include direct grant assistance for businesses or nonprofits, despite requests from local leaders, and mainly funded state agencies spinning up for what would likely be years of recovery administration.

Complicating matters, many small business owners in Western North Carolina had hoped for grants — not additional loans — because they were still carrying debt from COVID-19 and previous disasters.

The third bill, passed four weeks after the second, allocated another $227 million to the Helene fund but was condemned by Western legislators as “shameful” for including provisions that limited the powers of the incoming Democratic governor and attorney general while again putting no actual recovery money on the street.

That December, after Cooper and a delegation traveled to the White House with a $25 billion request, Congress failed to deliver adequate assistance, carving out an estimated $9-$15 billion from a $100 billion last-minute disaster relief bill that also provided support for New Mexico wildfires and the Key Bridge collapse in Baltimore. Although Western North Carolina’s Republican congressman Chuck Edwards sits on the House Appropriations Committee and claims to have penned the bill, he has never responded to Smoky Mountain News inquiries about why the funding was so scant.

The fourth relief bill passed by the General Assembly — the first of 2025, and the first signed by new Gov. Josh Stein — allocated an additional $275 million from the rainy day fund to the Helene fund and made targeted appropriations of $500 million.

The most recent bill, signed on the nine-month anniversary of the storm, appropriated $700 million in previously allocated funds and made an additional $575 million in appropriations, bringing the state’s total Helene recovery allocation to nearly $2 billion.

But as all that was happening, most county and municipal governments with storm losses still hadn’t seen a nickel of promised funds. Some governments even paid for projects out of their own reserves — with no explicit guarantee of reimbursement — because they simply couldn’t wait for the projects to be obligated by FEMA.

While formal funding channels slogged through bureaucratic bottlenecks, community-based nonprofits with far less resources than local government units were at the bottom of the list. The foundation moved in quickly to help — thanks in large part to the trust it had built over decades with both donors and partner organizations. Within two days of the storm’s landfall, the foundation had opened its emergency fund with no working phones, no power and no mail service.

“Leadership immediately opened the Emergency and Disaster Response Fund to receive donations,” said Carter Webb, a board member since 2022. “By Oct. 4, it had awarded the first grants. The quick turnaround was possible because of the experience and dedication of the foundation staff.”

Major funders like the Leon Levine Foundation, the Duke Endowment and Dogwood Health Trust contributed millions within days. Donations arrived from all 50 states and abroad. In the early weeks, grants went out twice daily. Once the immediate crisis stabilized, the foundation continued to process grants daily but shifted to weekly announcements, maintaining an online database of every award made.

In total, the foundation received more than $39.5 million in Helene-related donations and granted out more than $38.6 million by September 2025. That pace of giving dwarfed the scale of Tropical Storm Fred’s philanthropic response and challenged the organization’s internal capacity in new ways.

Because much of the region remained without reliable internet access for weeks after the storm, the foundation made accommodations for Spanish-speaking applicants and those who couldn’t access the online portal. Applicants were allowed to text their responses, or have staff enter data on their behalf. Rapid access to banking information from trusted nonprofit partners allowed the foundation to deposit funds directly, avoiding the need for checks or physical deliveries.

Without functioning infrastructure, many smaller counties struggled to organize a response.

To avoid overlap and maximize impact, the foundation coordinated closely with other funders. Working relationships with Dogwood, WNC Bridge Foundation and the North Carolina Community Foundation helped streamline efforts and reduce redundancy.

As of Sept. 11, the foundation’s disaster response fund has awarded 527 grants worth $39.6 million to Hurricane Helene recovery efforts across the region. The average award stands at just over $75,000, with grants reaching every county in Western North Carolina. The first awards were issued to groups like Centro Comunitario Hispano-Americano for Latino families in Henderson and Transylvania counties. One notable award was a $250,000 grant to Mountain Housing Opportunities in May 2025, supporting home repairs and wraparound services for displaced residents. Together, the grants reflect a yearlong flow of aid aimed at rebuilding homes, restoring services, and stabilizing vulnerable communities. Grant sizes range from $1,000 for the Burke County Literacy Council to multimillion-dollar allocations for major relief agencies.

The largest grant the foundation made — the largest grant the foundation has ever made — went to MANNA.

“We lost everything,” Nesbitt said. “We had a lot to do to get up and running and feed people.”

Just days after the storm, operating out of a temporary space at the WNC Farmer’s Market, MANNA began to do just that. The need, she said, was incredible, causing traffic jams up and down Brevard Road, out onto Interstate 26.

The initial effort was buoyed by a substantial grant from the Dogwood Health Trust and a live appearance from Good Morning America personality Al Roker, but he wasn’t the only celebrity who took note.

“Luke Combs, he and his wife called like the end of that first week in October and said that they personally wanted to help,” said Nesbitt.

The result was an all-star benefit concert in Charlotte on Oct. 26, 2024, organized by the country music superstar. Carolina Panthers owner David Tepper lent Combs Bank of America Stadium, free of charge. Performances by Combs, Eric Church, the Avett Brothers, Billy Strings and James Taylor, among others, raised more than $24 million for hurricane relief. MANNA’s cut was $3.2 million.

“Combs grew up in Asheville, just down the road from where MANNA used to be,” said Nesbitt. “He said that he and his mother would walk to MANNA from their house to volunteer when he was a kid.”

But as winter set in, MANNA still needed a permanent home, and the money to upfit.

“We needed money towards our freezer/cooler, a generator, sprinkler system, permanent racking, reach trucks. I mean, just such fundamental needs,” said Nesbitt.

The foundation stepped in, and in partnership with the North Carolina Community Foundation granted $7 million to MANNA — $3.5 million each.

“The damage to MANNA’s facility, equipment and food storage was complete and threatened food access for more than 220 partner agencies, 100 schools and potentially hundreds of thousands of people,” said Tara Scholtz, the foundation’s vice president for programs. “MANNA is the hub of food distribution for 16 of the foundation’s 18 counties and time was of the essence to get it back up and running.”

Asked if there were any other viable options for MANNA to raise those funds through state or federal agencies, Nesbitt’s response was only one syllable.

“No.”

From past experience, the foundation understood its role was not to replace government aid, but to move faster and more flexibly where government aid hadn’t yet arrived.

“Community foundations are uniquely positioned to respond in times of crisis and have a history of moving quickly and utilizing trusted relationships to get funds where they are needed,” said Elizabeth Brazas, president and CEO of the Community Foundation of Western North Carolina. “With the support of many philanthropic partners and generous people, CFWNC was able to get money out fast and first, but philanthropy cannot meet the deep and substantial needs that Helene caused in WNC.”

The sheer volume of demand and the absence of an immediate, coherent financial presence by state and federal government agencies meantthe foundation had to think big — and fast.

In Yancey County, for example, a student died, an elementary school was rendered unusable, and dozens of staff lost homes or vehicles. The foundation issued $20,000 grants to each school in the affected districts in Avery, Mitchell and Yancey counties. These block grants eliminated the need for multiple applications and helped school leaders focus on reopening rather than navigating red tape.

Grants also flowed to the Western Region Education Service Alliance, to help school staff with personal losses, and to Working Wheels, which helped repair or replace vehicles for storm victims and provided service vehicle repairs for frontline nonprofit partners. Other organizations, including arts councils, craft cooperatives and tourism nonprofits received support to recover from losses that were economic as well as physical, although lost revenue and payroll weren’t covered.

As the weeks passed, the nature of the foundation’s role came to include both immediate relief and long-term recovery. A $2 million grant to the Bridging Together Project in mid-November supported Lutheran and Mennonite volunteers working to replace private bridges that had isolated entire communities. Historically, private roads and bridges have not been eligible for FEMA funds, and initially, state funding was absent.

Those bridges, built using pre-engineered designs, were cheaper and more flood-resilient than traditional models, ensuring greater safety in future storms.

Another $850,000 was awarded to Fuller Center Disaster Rebuilders, a group leading a permanent housing development in Black Mountain for displaced residents. Built under a community land trust model, the homes will remain affordable in perpetuity.

These kinds of strategic investments reflect a deepening of the foundation’s approach — a recognition that short-term relief must give way to long-term resilience, and that resilience itself will require collaboration, innovation and sustained funding.

But with other, more recent disasters competing for public headspace and philanthropic resources, questions remain about what happens next for Western North Carolina.

While the foundation remains committed to staying engaged even after EDRF funds are depleted, there is no expectation that it can — or should — take over responsibilities traditionally held by the state or federal governments.

Throughout Helene recovery, residents and businesses encountered government systems that were slow, inflexible or inaccessible to many rural communities. Aid delayed by procedural hurdles left nonprofit partners scrambling to meet basic needs.

Operating in this environment, the foundation maintained strict internal controls over grantmaking. With fraudulent AI-generated applications on the rise, the foundation relied on its relationships to help verify submissions.

“Once we started to identify fraudulent applications, we slowed our process to add additional due diligence,” Scholtz said. “We relied on our existing relationships, other funders and resources like the state and federal VOAD lists to establish validity. We also started to require documentation of partnerships with established WNC providers if the applicant was out of state.”

The foundation saw itself not just as a pass-through for donor generosity, but as a responsible steward of public trust.

That trust extended beyond donors. In some communities, the foundation became a clearinghouse of sorts — not only for money, but for logistical information. Foundation staff collaborated with funders, maintained relationships with regional VOADs and helped support best practices, including the use of a multi-agency warehouse to distribute supplies from outside the disaster zone to declared counties.

In the process, the foundation found itself not just responding to Helene, but adapting in real time to lessons it had never been forced to learn before.

Despite its success in navigating disaster relief, foundation leaders are clear-eyed about their limitations. The intense pace of daily grantmaking after Helene was physically and emotionally exhausting. Staff worked from parking lots and fire stations, piggybacking on library Wi-Fi and coordinating with state and national funders through improvised channels.

“The work was intense, but we were buoyed by the donations that flowed in and understood the need for dollars to get out quickly,” said foundation Communications Director Lindsay Hearn. “Having a conference room at a local hotel during the first two weeks was key to our ability to accept and distribute resources. It had power, Wi-Fi, water — not potable — and, if we ran up to the top of their parking garage, the occasional cell signal.”

Much of that early work was possible because the foundation had already built a foundation of trust—not just with grantees, but with other institutions like Dogwood, which immediately put $10 million into the response. That level of funding and coordination is rare, even for large community foundations.

While Helene showed what’s possible when philanthropy moves with speed and confidence, it also exposed the fragility of relying on nonprofits to shoulder long-term recovery on short-term funding.

To date, more than 10,000 individual donations have flowed into the disaster response fund —from major endowments, yes, but also from children’s lemonade stands, high school swim teams, whisky distillers and seafood restaurants on the coast.

The outpouring of generosity has been remarkable, but generosity alone is not a strategy.

As Helene’s anniversary approaches — 20 years after Hurricane Katrina — the question looming over Western North Carolina is no longer how much damage was done. The model the foundation helped create, a nimble, trusted, locally embedded partner that can move faster than the speed of government, is both inspiring and unsettling.

Inspiring, because it works. Unsettling, because it suggests that systems built to protect the public can no longer be counted on to function as designed.

Whether this role for community foundations is sustainable remains unclear.

Over the past 20 years, financial records from the foundation show steady growth in both revenue and philanthropic activity. Since 2004, total revenue has more than quadrupled, peaking at $45.5 million in 2022, with contributions and investment income acting as the primary drivers. Contributions reached a high of $30.7 million that year.

“The foundation has focused on its sustainability so that we can respond to the changing needs in WNC. We have to be here and be resilient so that our fundholders can continue to support our nonprofit partners, especially as funding cuts impact the services that people depend on,” Brazas said. “While CFWNC funding is impacted by the economy, we have seen our fundholders and donors rise to the occasion time and again to help their neighbors and communities in times of crisis, including prolonged economic downturns.”

On the expenditure side, grants and similar payments consistently made up the largest portion of total expenses. In recent years, the foundation granted roughly $20 million annually, with a pre-Helene record $20.9 million in 2022.

Salaries and benefits, increasing modestly over time, have remained under $3 million annually, suggesting lean administrative overhead. Net assets have steadily climbed from $99 million in 2004 to more than $320 million by 2024, signaling strong stewardship and sustained donor trust.

This financial trajectory highlights the foundation’s growing capacity to support regional needs, particularly during crises, but it’s not perfect and it’s not permanent.

The Great Recession began in late 2007, after the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble triggered a wave of mortgage defaults that cascaded through the global financial system and led to the failure of major banks. Not coincidentally, during 2008 the federal funds interest rate went from 4.25% to nearly zero — great for borrowers, not so great for investors.

For the year ending June 30, 2009, the foundation posted a negative $6.9 million in investment income, a figure that had generally been a positive $2-3 million in prior years.

As the Great Recession wore on, it would take until 2012 for the foundation’s investment income to reach previous levels. Contributions and grants slumped. In 2007 and 2008, those income streams were $13.7 million and $14.7 million, respectively. For that same 2009 reporting period, they slipped to $8.3 million. As with investment income, it wasn’t until 2012 that the foundation was able to surpass pre-recession revenue.

Consequently, grant activity slowed over the same period. In 2008, the organization granted $12.3 million, its highest total until 2015’s $13.2 million. In 2009, grants fell to $8.7 million.

Net assets also took a hit. In 2008, they were just under $122 million. In 2009, they were $96.5 million.

“Giving patterns change when there are extended downturns in the economy,” said foundation CFO Graham Keever, “but CFWNC has been intentional about building reserves during strong economic times which enables us to sustain operations during inevitable economic downturns.”

Never wavering in its mission, the foundation recovered impressively — despite a minor downturn during COVID — however, it’s clear that a badly-timed economic slump coupled with a major disaster would impact giving, and therefore recovery, in a region that already faces challenges.

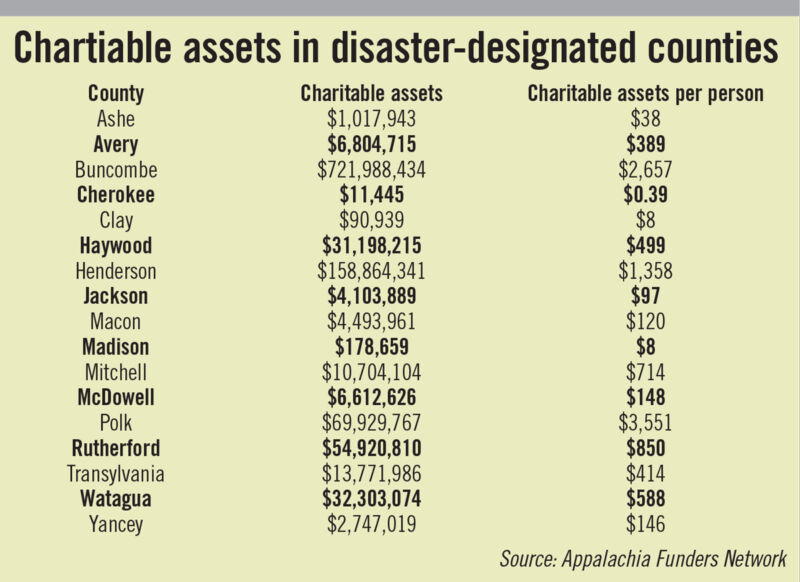

The Appalachia Funders Network, which connects funders working collaboratively to build equity, health and prosperity across Appalachia, released a startling report this past May on philanthropic inequity in central Appalachia, a region made and kept relatively poor by decades of extractive economic activity. Among the most troubling conclusions are that dozens of the 236 counties in the six-state region have little to no nonprofit presence and 31 don’t have an active community foundation at all.

Urban counties in the Central Appalachia region have an average of $973 in charitable assets per person. Rural counties average $273. More than $390 million in grants were given in urban counties. Only $16 million made it to rural counties.

Most, but not all, of the counties affected by Helene are rural.

According to the report, 55% of philanthropic investment in the San Francisco Bay area comes from within the region, while in Central Appalachia, nonprofits are more reliant on outsiders. Just 27% of investment comes from within the region.

Without early and aggressive intervention by Western North Carolina’s nonprofit ecosystem, recovery in the mountains would have taken far longer and cost far more — in lives and in livelihoods, in time and in trust.

In a historically poor region dependent on outside funding and subject to economic downturns, it wasn’t the first time the Community Foundation of Western North Carolina had stepped into the void left by formal disaster response systems. It probably won’t be the last. Philanthropy helped Western North Carolina survive. The question now is whether philanthropy alone can help it endure.

“The generosity continues, but giving has slowed,” said Brazas. “We are committed to making sure the funds that come here continue to support recovery. Progress has been made, but rebuilding is going to take years and much more investment.”

This article was reported through a fellowship supported by the Lilly Endowment and administered by the Chronicle of Philanthropy to expand coverage of philanthropy and nonprofits. The Smoky Mountain News is solely responsible for all content.